- Published on

Commercially Available Information & How the Government Buys Your Personal Data

- Authors

- Name

- Weslen T. Lakins

- @WeslenLakins

Introduction

Ever wondered how much the government knows about your life? Picture this: your morning weather check,1 that fitness app tracking your runs,2 or even your favorite dating app3—these seemingly mundane activities are treasure troves of data. Now, imagine if the government could buy this information without your consent or a warrant. Sounds like something out of a dystopian novel, right? Unfortunately, this has been our reality.4 But things are changing.5

The world of data privacy has been buzzing with significant developments lately.6 While we always knew big brother was watching, a 2022 report to the Director of National Intelligence (DNI)7 revealed just how deep the rabbit hole goes, igniting a firestorm of public and legislative scrutiny.8 Now, with the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act having cleared the House and likely to pass the Senate,9 the Intelligence Community (IC) has released a new "Commercially Available Information (CAI) Framework"10 to navigate this evolving terrain. Turn on your VPNs, and let's unpack what this means for our privacy.

2022 ODNI Senior Advisory Group Panel on CAI Report

Make no mistake, we now live in a world where every step you take, every place you visit, and almost everything you do online leaves a trace—a digital footprint that can be bought and sold like any other commodity. As detailed in a recently declassified report on CAI commissioned by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) and directed to Avril Haines, the DNI, there have been profound changes in how intelligence is gathered.11

So, what exactly is CAI? The term refers to data that is commercially available to the public. This might sound straightforward, but it's actually a complex and ever-evolving landscape. CAI encompasses a vast array of information—everything from location data harvested from smartphones to detailed consumer profiles built from online behaviors.12 Essentially, if you’ve ever agreed to the terms and conditions of an app without reading them (and let's face it, who hasn’t?), you’ve likely contributed to this pool of data.13

The report starts with a fundamental question: How does the IC use CAI, and what are the implications? It turns out that the IC relies heavily on CAI for intelligence collection and analysis. The value of CAI lies in its ability to provide insights that are often difficult, if not impossible, to obtain through traditional intelligence methods.14 This data is used for a variety of purposes, including national security, counter-terrorism, and even humanitarian assistance. For instance, during natural disasters, CAI can help track human mobility and assess the impact on populations.15

However, this treasure trove of information comes with significant risks, particularly concerning privacy and civil liberties. The report highlights a critical issue: while CAI is less strictly regulated than other forms of intelligence, its scope and sensitivity have dramatically increased. Modern CAI is not just about what is public—it’s about the depth and detail of information available. This includes highly sensitive data like precise location tracking, personal habits, and intimate details about individuals’ lives. The potential for misuse is immense, raising concerns about privacy, civil liberties, and the risk of government overreach.16

To address these concerns, the report makes three key recommendations. First, the IC needs to develop a comprehensive, multi-layered process to catalog CAI. This isn’t just about keeping a list of what data is collected; it’s about understanding the entire lifecycle of this information—from acquisition to use to storage.17 This effort will require a deep dive into procurement contracts, data flows, and how data is ultimately used by various IC elements.

The second recommendation calls for the development of adaptable standards and procedures for handling CAI. Given the diverse needs and missions of different IC elements, a one-size-fits-all approach won’t work. Instead, the IC should establish a set of guidelines that can be tailored to specific contexts while maintaining a consistent core of principles. This includes regular re-evaluation of how CAI is acquired and used, ensuring that decisions are based on up-to-date information and current best practices.18

The third recommendation emphasizes the need for more precise guidance on sensitivity and privacy protection. The report argues that publicly available information (PAI) is no longer an adequate proxy for non-sensitive data. Today’s CAI is far more revealing and pervasive than traditional PAI. The IC must develop refined policies that recognize the unique sensitivity of modern CAI and implement measures to protect individuals’ privacy and civil liberties. This includes assessing the potential harms of data misuse and ensuring robust oversight mechanisms are in place.19

One of the most striking aspects of the report is its discussion on the balance between intelligence value and privacy risks. The IC faces a challenging dilemma: while CAI is incredibly valuable for intelligence purposes, it also poses significant risks if not handled correctly. For example, location data from smartphones can provide crucial insights for tracking terrorist movements or planning military operations. But the same data, if misused, can invade individuals' privacy to an alarming degree, revealing intimate details about their daily lives and personal relationships.20

The report also touches on the legal landscape surrounding CAI. Under current U.S. law and IC guidelines, CAI is generally treated as non-sensitive because it is publicly available. However, the Supreme Court’s decision in Carpenter v. United States, which requires a warrant for accessing historical cell-site location information, signals a shift towards greater privacy protections for certain types of data.21 The IC must navigate this evolving legal environment, balancing the need for intelligence with the rights of individuals.

In conclusion, the declassified report on CAI paints a complex picture of the modern intelligence landscape. The proliferation of digital data presents both unprecedented opportunities and significant challenges. The IC must adapt its policies and practices to harness the value of CAI while protecting privacy and civil liberties. By developing comprehensive cataloging processes, adaptable standards, and precise sensitivity guidance, the IC can navigate this new frontier responsibly.22 The report’s recommendations are a crucial step towards ensuring that intelligence practices keep pace with the rapid evolution of digital technology and the changing expectations of privacy in the 21st century.

Commercial Data Brokers Relationship with the IC

Commercial data brokers collect and sell information about us collected from photos posted to social media, historic geolocation data collected by our cell phone apps, banks, credit agencies, purchase history, education records, employment records, property records and real-time location.23 These data points are among billions archived in public and private sources. This personal data is mined by third-party vendors and data resellers, then aggregated and analyzed by data brokers who in turn look for buyers of its troves of profiles.24

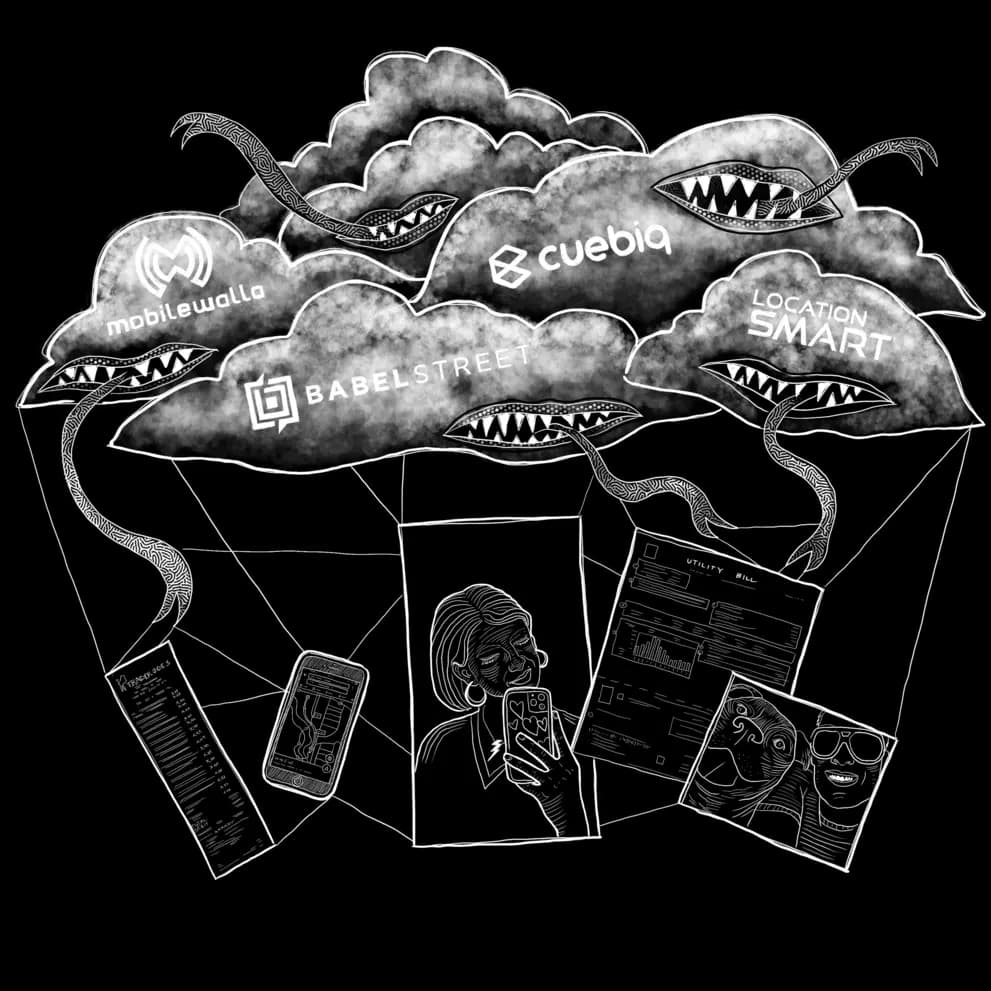

In other words, if you have a cell phone, your personal data is likely being sold by multiple companies whose names you’ve likely never heard.25 So-called “third-party vendors” or data brokers like Venntel, Babel Street, Cuebiq, and LocationSmart collect real-time location data via GPS.26 They monitor your activities and movements through your phone via benign-seeming apps that use software development kits (SDKs). Apps that use SDKs include weather apps, exercise monitoring apps, and video games. Third-party vendors provide SDKs to app developers for free in exchange for the information they can collect from them, or a cut of the ads they can sell through them.27 The aggregate information that apps collect can be extremely revealing. One third-party vendor, Mobilewalla, claimed to be able to track cellphones of protesters, and said it could identify protesters’ age, gender, and race via their cell phone use.28 Historical location information extracted by a data vendor from the gay hookup app, Grindr, was used by two reporters to “out” a top Catholic Church official.29

Law enforcement purchases criminal history reports, financial data from credit bureaus, and other personal data to profile people. For example, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) purchases access to the Venntel global mobile location database via a portal, so that CBP officers search a Venntel database to look for addresses or cell phone numbers.30 The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) can also access cell phone location history from private databases that sell subscriptions or search platforms, such as LexisNexis and TransUnion.31

Some experts have noted that “anonymized” GPS location data is notoriously easy to cross-reference.32 A New York Times op-ed posed the question: “Consider your daily commute: Would any other smartphone travel directly between your house and your office every day?”33 The authors concluded: “In most cases, ascertaining a home location and an office location was enough to identify a person.” More recently, cell phone location “pings,” collected by apps and stored under profiles tied to mobile ad IDs that are assigned to smartphones, were sufficient to identify individuals who ransacked the Capitol building in Washington, D.C., on January 6.34 And the use of “geo-f

encing,” i.e., obtaining information from private companies about all persons in an area at a given time, has become exponentially more common in recent years.35

The Databases Used by the IC

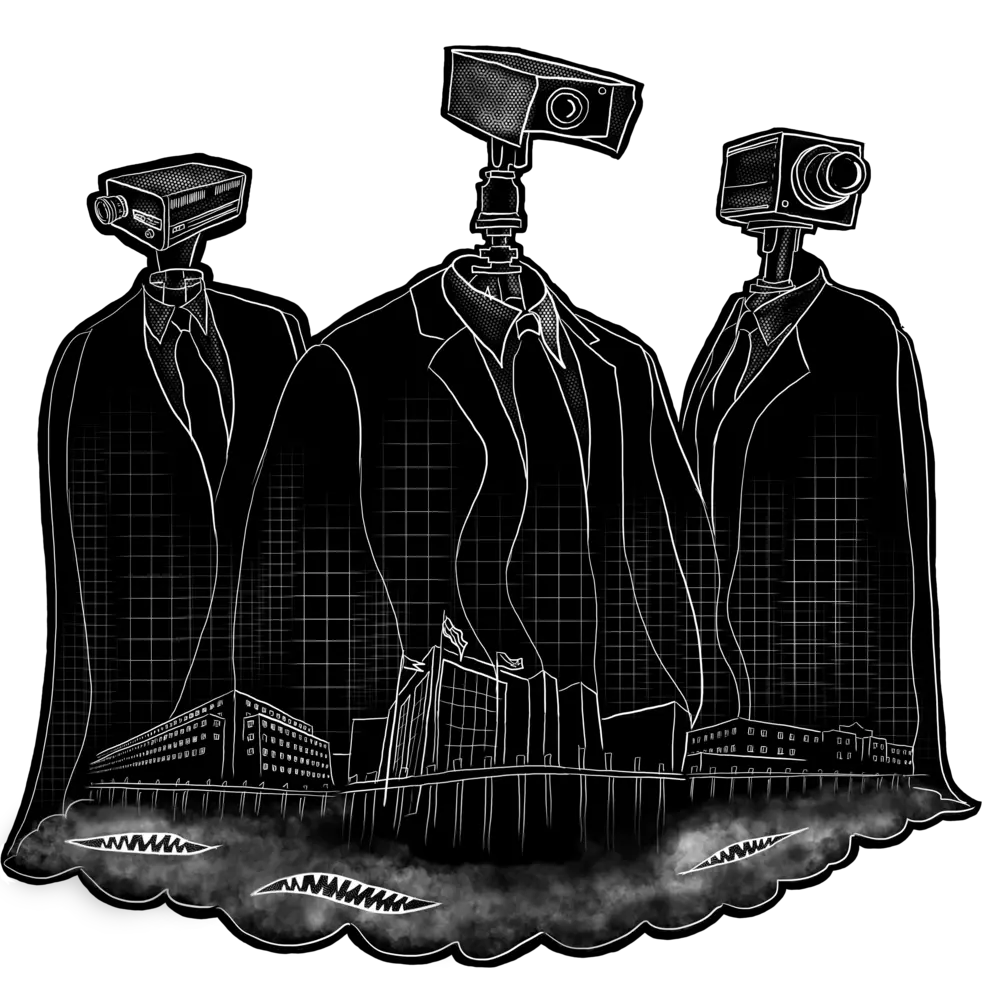

The IC uses a variety of databases to store and analyze data collected from various sources, including CAI. These databases play a crucial role in intelligence gathering, analysis, and dissemination, providing analysts with the tools they need to make informed decisions and protect national security.

Advanced Passenger Information System (APIS)

APIS is an electronic data system that allows commercial airlines to transmit traveler data directly to CBP.36

Before a person can board a flight to, from, or overflying the US, their passport or ID is scanned by a CBP officer or Transportation Security Administration (TSA) agent. The machine-readable zone of their document pulls up their full name, date of birth, and citizenship, which can be used to retrieve information about their scheduled flight.37 This data is sent to CBP via APIS in the form of “passenger manifests” — commercial airline records that are transferred to CBP for vetting in real-time, or 30 minutes prior to boarding.38

Upon transmission, APIS data is immediately sent to other CBP databases, including TECS/ ICM for cross-referencing and storage. APIS generates an “Overstay Lead” list that is shared with CBP’s main computer system that predicts “risk,” Automated Targeting System (ATS). Simultaneously, APIS is screened against the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Terrorist Screening Center’s Terrorist Screening Database (TSDB).39

Analytical Framework for Intelligence (AFI)

AFI is a Palantir tool that uses profiling algorithms created for former President Trump’s “Extreme Vetting” initiative to “detect trends, patterns, and emerging threats, and identify non-obvious relationships between persons, events, and cargo.”40 Knight and Gekker, “Mapping Interfacial Regimes of Control”; Medina and Customs, “Privacy Compliance Review of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Analytical Framework for Intelligence (AFI) December 6, 2016,”

According to a 2012 Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) on AFI, “data is indexed so that the system may retrieve it by any identifier maintained in the record. As information is retrieved from multiple sources it may be joined to create a more complete representation of an event or concept. For example, a complex event such as a seizure that is represented by multiple records may be composed into a single object, for display, representing that event.”41 In this way, AFI offers data visualization, and creates an index.

Among other data points, AFI uses and stores public records showing who owns land near the US-Mexico border, and ingests records on “individuals not implicated in activities in violation of laws enforced or administered by CBP but with pertinent knowledge of some circumstance of a case or record subject,” as well as those not accused of breaking immigration or other laws but who might have “knowledge of narcotics trafficking or related activities.”42 In 2019, AFI made headlines when NBC reported that AFI was being used to mine US citizens’ social media posts on “caravans” and political rallies in order to train its targeting algorithm.43

AFI provides tools like geospatial, temporal and statistical analysis, and advanced search capabilities of commercial databases and Internet sources, including social media and traditional news media.44 Like other DHS systems, AFI automatically collects and stores criminalizing data from travel records in ATS-UPAX, ESTA, ADIS, ICM/ TECS, records from immigration arrests and deportations, and lists of foreign students. AFI also copies volumes of such government data onto its own (Palantir) servers.45 AFI uses Apache Hadoop, an open-source framework that allows for faster searching across big datasets, which is hosted on the Amazon cloud. Hadoop requires continuous replication of data stored in multiple locations as well.46

National Crime Information Center (NCIC)

NCIC is a computerized index and central federal database for open warrants, wants, and “lookouts” for people and allegedly stolen property. It is the main criminalizing database at the national level, described as the "lifeblood of law enforcement."47 NCIC is maintained by the FBI and overseen by the agency’s Criminal Justice Information Services division. It is named after the NCIC where it is housed in Clarksburg, West Virginia.48

As law professor Bridget A. Fahey writes, "Any person who has been subject to a traffic stop — or seen one in a movie — knows about the NCIC in practice if not in name. When police officers run a name, driver’s license, or license plate, they search the NCIC, a sprawling repository of information about crime across levels of government to which 'virtually every criminal justice agency nationwide' has access and contributes data. The NCIC supports 'millions of transactions each day.' And a survey of states estimated that the entire sweep of networked criminal history databases contains files on 110 million people."49

NCIC criminal history data (which includes arrest records even when there isn’t a conviction) is submitted directly by the arresting law enforcement agency.50 If you are subjected to a background check or “criminal check,” chances are high that NCIC is consulted. Because it is the go-to source for criminalizing data, it is noteworthy that since 2001, NCIC records make visible civil immigration information, including prior removal orders, and allows Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) analysts at its Law Enforcement Support Center (LESC) to tag people as “Immigration Violators” in the NCIC system and/or mark their record with an outstanding criminal or administrative warrant — so that if a cop looks up a tagged person, the note will show up.51

Next Generation Identification (NGI)

The FBI’s NGI, formerly Department of Justice Criminal Justice Information Services Division Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System (IAFIS), is purportedly the largest electronic repository of biometric information in the world.52

While historically, “biometrics” refers to fingerprints, today the category includes experimental modalities including palm prints, voice prints, irises, and facial recognition.53 NGI includes fingerprints that have been sent to the FBI via the criminal legal system primarily, by states, territories, and federal law enforcement agencies. If you’ve ever been arrested before, you would be listed in NGI.54

NGI is used by ICE in the field to quickly check a person’s biometrics against criminal legal history — especially if a person’s biometrics cannot be found in DHS’ IDENT database.55

ICE agents use EAGLE to submit biographic information, fingerprints, and arrest information to NGI for storage and for fingerprint-based criminal records checks. NGI sends back to EAGLE the results of the fingerprint check, including any criminal history information or wants and warrants on the individual.56

In the field, ICE officers can use the mobile device, EDDIE, to query simultaneously NGI for criminal history information and IDENT for a person’s immigration history. In response to the query, NGI and/or IDENT send a response, in less than a minute, to EDDIE indicating whether there is a fingerprint match. The NGI response includes a list of potential candidates who may match the prints submitted by EDDIE. NGI also provides the candidate’s Identity History Summary, which was formerly referred to as a “rap sheet.”57

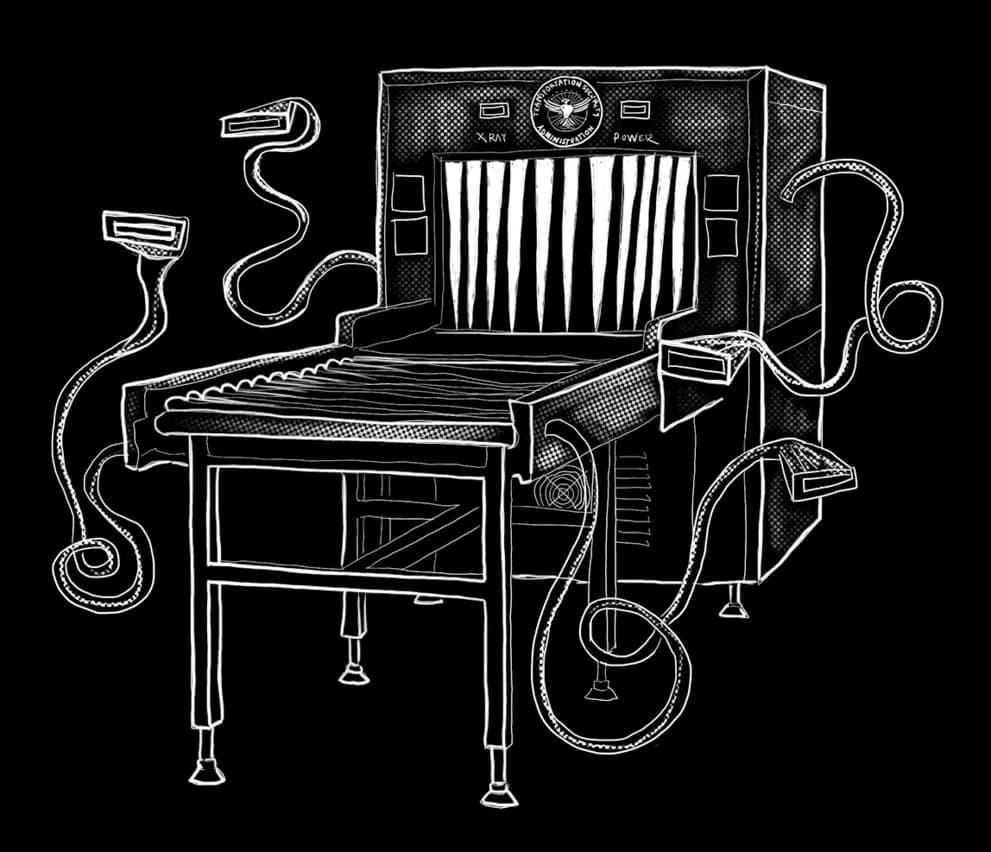

Secure Flight Passenger Database (SFPD)

In November 2001, then-President Bush signed the Aviation and Transportation Security Act into law, creating the TSA — a division of DHS that operates a travel-permission system for domestic US flights called “Secure Flight.”58

“Secure Flight” began as a program where aircraft operators screened names from passenger reservations to see if they matched or closely resembled any included on a “No Fly List” and other federal watchlists of “known or suspected terrorists” created by the FBI. If the aircraft operator suspected a watchlist match, the operators were supposed to notify TSA and send the targeted passenger for enhanced in-person screening.59

Today, “Secure Flight” allows TSA to access CBP’s surveillance dragnet and prediction tool — ATS, and write rules for the algorithm used by the ATS system to decide who qualifies as a “risk” and will be added to a category of people who will be subject to increased security checks. Targeting rules, and therefore the people targeted, can change day to day.60

The Fourth Amendment is Not for Sale Act

The Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act is a landmark piece of legislation designed to tackle the pressing privacy concerns raised by the extensive use of CAI by law enforcement and intelligence agencies.61 Passed by the House of Representatives in April 2024, this Act represents a significant shift towards restoring the balance between national security and individual privacy rights.62

At its core, the Act aims to amend Section 2702 of Title 18 of the United States Code, making it illegal for law enforcement and intelligence agencies to obtain subscriber or customer records in exchange for anything of value without a warrant.63 This includes data held by intermediary internet service providers, ensuring that such entities cannot divulge sensitive information to the government without proper judicial oversight. The goal is to close the loophole that previously allowed government agencies to purchase data from brokers, which they would otherwise need a warrant to obtain.64

The provisions of the Act are clear and decisive. By prohibiting the purchase of data without a warrant, the Act marks a return to stricter adherence to the Fourth Amendment, which protects citizens from unreasonable searches and seizures. It also imposes stringent limitations on the sharing of such data

between agencies, further tightening the reins on how personal information can be used and disseminated. This move is a direct response to the abuses highlighted in the 2022 DNI report, aiming to restore public trust and protect individual privacy.65

Support for the Act has been notably bipartisan, reflecting a widespread recognition of the need to protect privacy rights.66 Lawmakers from both sides of the aisle have acknowledged the importance of closing these surveillance loopholes, and the Act's passage in the House was celebrated as a significant victory for privacy advocates. However, the journey isn't over yet. With the Senate expected to pass the bill, attention now turns to the implementation and enforcement of its provisions. Ensuring that these new rules are followed will be crucial in safeguarding the privacy of American citizens.67

The Act's introduction and subsequent passage represent a broader legislative push to address the erosion of privacy rights in the digital age. It underscores a growing awareness among lawmakers and the public alike that the unchecked acquisition of personal data by the government poses a significant threat to individual freedoms. By requiring warrants for data purchases, the Act seeks to reestablish the constitutional protections that have been undermined by modern surveillance practices.68

As the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act moves closer to becoming law, its implications for privacy and surveillance in the United States are profound. The Act signifies a critical step towards restoring the balance between national security and individual privacy. However, its success will depend on rigorous implementation and enforcement. Ensuring that government agencies comply with these new rules is crucial in maintaining public trust and upholding constitutional protections.69

The IC's CAI Framework

The May 2024 Policy Framework for CAI from the ODNI offers a fascinating glimpse into how the U.S. IC is adapting to the realities of our data-saturated world.70 The framework tackles the immense task of balancing intelligence needs with the protection of privacy and civil liberties, a challenge made even more pressing by the sheer volume and sensitivity of data now collected through everyday devices.71

CAI includes data from cell phones, cars, and household appliances, all aggregated by commercial entities and sold to various buyers, including the IC.72 The framework recognizes the enormous value of CAI in providing critical intelligence, yet it also acknowledges the potential risks to individual privacy. This duality is at the heart of the new policy, which seeks to clarify how the IC can use CAI effectively while ensuring robust privacy protections.73

The policy begins by laying out some guiding principles. It insists that any access, collection, or processing of CAI must be legally authorized and tied to a validated mission or administrative need.74 This isn't just a matter of following the law; it's about aligning intelligence activities with clearly defined purposes. Privacy and civil liberties are central to this approach. The framework demands that these considerations be integral to every step of handling CAI, from the moment data is accessed to its final use.75

A significant part of the framework deals with the importance of understanding where the data comes from and how it was collected. IC elements are tasked with verifying the sources of CAI and assessing the methods used to gather and aggregate it. This is crucial for ensuring that the data's integrity and quality meet the high standards required for accurate and reliable intelligence.76

Another essential aspect of the framework is its stance on non-discrimination. The policy explicitly prohibits using CAI to disadvantage individuals based on ethnicity, race, gender, sexual orientation, or religion. It also bars the use of CAI to take adverse actions against someone for exercising their constitutionally protected rights.77 This principle is a clear recognition of the potential for misuse inherent in such vast data troves.78

When it comes to sensitive CAI, which includes data that contains substantial volumes of personally identifiable information (PII) or highly sensitive details about individuals, the framework introduces even stricter guidelines.79 Sensitive CAI is subject to heightened protections due to its potential to reveal detailed personal attributes and activities. For instance, if the data includes information about someone’s race, ethnicity, political opinions, religious beliefs, sexual orientation, or medical conditions, it must be handled with extreme care.80

Before accessing or collecting sensitive CAI, the IC must conduct thorough analyses to determine if the data supports an authorized mission, whether there is legal authority to collect it, and how sensitive the data is.81 This analysis also includes assessing privacy risks and considering privacy-enhancing techniques like anonymization. Every decision to access sensitive CAI must be approved by senior officials, ensuring accountability at the highest levels.82

Safeguarding sensitive CAI is another critical area. The framework mandates that sensitive data be kept in secure systems with proper access controls. The IC must evaluate existing safeguards and, if necessary, implement additional measures to mitigate risks.83 These could include restricting access to a limited number of personnel, conducting regular audits of data queries, and applying information masking techniques to protect privacy.84

The policy also emphasizes the importance of ongoing review and reassessment. IC elements are required to periodically re-evaluate whether they still need the sensitive CAI they have and whether the safeguards in place are adequate.85 This continuous monitoring helps ensure that privacy protections evolve alongside changing intelligence needs and technological capabilities.86

Additionally, transparency is a key theme throughout the framework. The IC is committed to providing clear documentation of its CAI activities and making this information available for oversight.87 Annual reports to the ODNI will detail all CAI procurements, and these reports will help promote best practices across the intelligence community.88 Additionally, the ODNI will provide biennial reports to the public to enhance understanding of how CAI is used and protected.89

In essence, the May 2024 Policy Framework for CAI represents a thoughtful and detailed approach to managing the vast amounts of commercially available data in a way that respects both the intelligence needs and the privacy rights of individuals. By establishing clear principles and stringent guidelines, the framework seeks to ensure that the IC can leverage the intelligence value of CAI while safeguarding the privacy and civil liberties of individuals.90 This approach reflects a nuanced understanding of the challenges and opportunities presented by modern data collection technologies and sets a precedent for responsible data management in the IC.91

Looking Ahead

The intricate dance between national security and individual privacy has never been more delicate than in the realm of CAI.92 The IC's reliance on CAI highlights its immense value for safeguarding national interests, yet it also underscores the significant risks to personal privacy and civil liberties.93 The recently declassified report and the subsequent policy framework from the ODNI provide a roadmap for navigating this complex terrain.94

The recommendations to develop comprehensive cataloging processes, adaptable standards, and precise sensitivity guidelines are crucial steps toward responsible management of CAI.95 These measures aim to strike a balance that allows the IC to harness the benefits of modern data technologies while mitigating potential abuses.96

The Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act represents a landmark legislative effort to reclaim privacy rights in the digital age.97 By closing loopholes that permitted unchecked data acquisition, this Act signals a return to the foundational principles of privacy and judicial oversight.98 Its successful implementation will be a critical milestone in ensuring that government agencies adhere to constitutional protections while performing their essential duties.99

In conclusion, the evolving landscape of data privacy requires constant vigilance and adaptation.100 As technology continues to advance, so too must our legal and ethical frameworks.101 The IC's proactive approach, combined with robust legislative action, paves the way for a future where national security and individual privacy are not mutually exclusive but are instead harmonized through thoughtful regulation and oversight.102 This balanced approach is essential for maintaining public trust and upholding the fundamental rights that define a democratic society.103

Footnotes

Popular Weather App Collects Too Much User Data, Security Experts Say, Wall St. J., https://www.wsj.com/articles/popular-weather-app-collects-too-much-user-data-security-experts-say-11546428914 (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Fitness Apps Are Tracking More Than Just Your Workout, Turnto10, https://turnto10.com/i-team/consumer-advocate/fitness-apps-are-tracking-more-than-just-your-workout (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Data-Hungry Dating Apps Are Worse Than Ever for Your Privacy, Mozilla Foundation, https://foundation.mozilla.org/en/privacynotincluded/articles/data-hungry-dating-apps-are-worse-than-ever-for-your-privacy/ (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Federal Agencies Are Secretly Buying Consumer Data, Brennan Ctr. for Just., https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/federal-agencies-are-secretly-buying-consumer-data (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Congress Looks to Block US Agencies From Buying Americans’ Data, Roll Call, https://rollcall.com/2023/12/12/congress-looks-to-block-us-agencies-from-buying-americans-data/ (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Stop the Government’s Massive Privacy Invasion, ACLU, https://action.aclu.org/send-message/stop-governments-massive-privacy-invasion (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Office of the Dir. of Nat’l Intelligence, Declassified Report on CAI (Jan. 2022), https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ODNI-Declassified-Report-on-CAI-January2022.pdf (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Stop the Government’s Massive Privacy Invasion, supra note 6. ↩

House Passes Bill Requiring Warrant to Purchase Data from Third Parties, The Hill, https://thehill.com/homenews/house/4601266-house-passes-bill-requiring-warrant-to-purchase-data-from-third-parties/ (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

ODNI Releases IC Policy Framework for CAI, Office of the Dir. of Nat’l Intelligence, https://www.dni.gov/index.php/newsroom/press-releases/press-releases-2024/3815-odni-releases-ic-policy-framework-for-commercially-available-information (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Office of the Dir. of Nat’l Intelligence, supra note 7. ↩

Id. ↩

Federal Agencies Are Secretly Buying Consumer Data, supra note 4. ↩

Office of the Dir. of Nat’l Intelligence, supra note 7. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Carpenter v. United States, 138 S. Ct. 2206 (2018). ↩

Id. ↩

Office of the Dir. of Nat’l Intelligence, supra note 7. ↩

Federal Agencies Are Secretly Buying Consumer Data, supra note 4. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Mobilewalla’s Analysis of Protester Data, Mobilewalla, https://www.mobilewalla.com/blog/analyzing-data-protests (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Grindr Data Led To The Ousting Of A Top Catholic Church Official, N.Y. Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/21/us/grindr-priest-resignation.html (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Congress Looks to Block US Agencies From Buying Americans’ Data, supra note 5. ↩

Federal Agencies Are Secretly Buying Consumer Data, supra note 4. ↩

Grindr Data Led To The Ousting Of A Top Catholic Church Official, supra note 29. ↩

Id. ↩

Location Data Shows How the Capitol Riot Unfolded, N.Y. Times, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/01/12/us/capitol-mob-map.html (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Id. ↩

Advanced Passenger Information System, U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., https://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/privacy/privacy_pia_cbp_apis.pdf (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Analytical Framework for Intelligence, Palantir, https://www.palantir.com/platforms/foundry/afi/ (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Privacy Impact Assessment for the Analytical Framework for Intelligence, U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., https://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/privacy/privacy_pia_cbp_afi.pdf (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Id. ↩

ICE Using Vast Surveillance Dragnet to Mine US Citizens’ Social Media Posts, NBC News, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/ice-using-vast-surveillance-dragnet-mine-us-citizens-social-media-n1047966 (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Privacy Impact Assessment for the Analytical Framework for Intelligence, supra note 41. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

NCIC, FBI, https://www.fbi.gov/services/cjis/ncic (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Id. ↩

Bridget A. Fahey, The Hidden Architecture of Criminal Law, 118 Mich. L. Rev. 85, 91 (2019). ↩

NCIC, supra note 47. ↩

Id. ↩

NGI, FBI, https://www.fbi.gov/services/cjis/fingerprints-and-other-biometrics/ngi (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Secure Flight, Transp. Sec. Admin., https://www.tsa.gov/secure-flight (last visited Dec. 13, 2023). ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Congress Looks to Block US Agencies From Buying Americans’ Data, supra note 5. ↩

House Passes Bill Requiring Warrant to Purchase Data from Third Parties, supra note 9. ↩

Congress Looks to Block US Agencies From Buying Americans’ Data, supra note 5. ↩

Id. ↩

Office of the Dir. of Nat’l Intelligence, supra note 7. ↩

Congress Looks to Block US Agencies From Buying Americans’ Data, supra note 5. ↩

House Passes Bill Requiring Warrant to Purchase Data from Third Parties, supra note 9. ↩

Congress Looks to Block US Agencies From Buying Americans’ Data, supra note 5. ↩

Id. ↩

ODNI Releases IC Policy Framework for CAI, supra note 10. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Congress Looks to Block US Agencies From Buying Americans’ Data, supra note 5. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩

Id. ↩